CLICK HERE to listen to the author read her article.

Since our founding, American society has shared a common belief system, morals, societal norms and language. It no longer does. While the people who formed the great melting pot of yesteryear maintained aspects of their unique cultural identities, every new wave of immigrants proudly assimilated and embraced what it was to be an American. Now, in a modern Trojan horse scenario with a twist, many people come to America hating everything we stand for. They take our handouts while using the freedom we give them as a weapon against us.

Along the way, we’ve sacrificed our Constitutional rights and privacy to continually placate those who never have, and never will, understand American exceptionalism. We have allowed our history and traditions to become the stuff of microfiche in musty libraries. Popular stories, songs, and poetry that were once so important to our identity have fallen by the wayside. One envisions Grandpa sitting by the fireplace recalling his favorite episodes of Duck Dynasty as he imparts some post-apocalyptic American history lesson to his grandchildren.

While it can always be said that a gulf exists between each generation, at the base of our Americana patchwork quilt there was a common thread that bound us together — despite changing fashions, music, and politics: we learned about our vast country through the same stories, poems, and songs. If they weren’t learned at home, they were taught in our schools.

What kid, for instance, didn’t know the travails of Mudville and Casey at the Bat? How many old-timers, voices trembling with age, could still dramatically deliver the lines:

Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt; Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt. Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

Defiance gleamed in Casey’s eye, a sneer curled Casey’s lip.

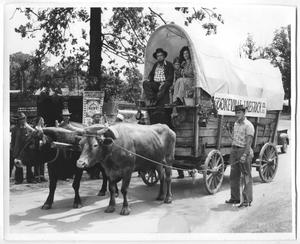

Who hadn’t imagined themselves on the shores of Gitche Gumee contemplating the adventures of Hiawatha and his lover Minnehaha? There wasn’t one person who couldn’t call to mind Johnny Appleseed, walking the countryside while randomly dropping seeds from a bulging sack slung over his shoulder. Everyone could tell you some exploit of Daniel Boone or Davy Crockett, or that Mike Fink was a bully who couldn’t be trusted. Was there anyone, anywhere, who didn’t know that Paul Bunyan had a blue ox named Babe or that John Henry was a steel-driving man? What little girl didn’t want to dress up like Pocahontas when it was still considered a tribute to a courageous woman instead of a politically incorrect stunt?

No one wove a yarn like Mark Twain, and most people could close their eyes and see Tom Sawyer and his whitewashed picket fence or Huckleberry Finn and Jim floating down the lazy Mississippi on a raft.

Folklore and oral traditions passed down through time were often history blended with legend. They were about real people and actual events so remarkable that they left an imprint on an era. Facts may have been stretched to impress the listener or reader, but these legends gave us insight into how people of the past lived: their real-life dangers and imagined fears, their strength in adversity, and their ability to love and laugh in the midst of despair.

By memorizing poetry, American children were taught that freedom came at a great price, “between the crosses, row on row” in Flanders Fields. They could never forget “the eighteenth of April in Seventy-five” when Paul Revere took his midnight ride. And while a 2006 Harris poll revealed that 2 out of 3 American’s didn’t know the lyrics to the Star Spangled Banner, children used to memorize the original poem, which contained socially unacceptable lines such as:

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our motto: “In God is our trust.”

Songs themselves used to be considered basic learning in our schools. Children learned all the verses to “America the Beautiful,” “Yankee Doodle,” and “This Land is Your Land” (minus some of Woody Guthrie’s political verses). In New York State, every kid had to know “Fifteen Years on the Erie Canal.” Somewhere along the way, every Tom, Dick, and Harry was bound to pick up “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,” “Red River Valley,” “Home on the Range,” and “Clementine.” How many of us, in our busy lives, have time to sing Polly Wolly Doodle all the day? And do you remember “Sweet Betsy from Pike”? (Right now you are likely trying to recall what she crossed the big mountains [or prairie] with. Hint: If you have an “old yeller dog” in there, you’re on a roll.)

Some of the sweetest songs ever to drift from the redwood forest to the Gulf stream waters came from Stephen Foster. Thanks to the Kentucky Derby, new generations learn “My Old Kentucky Home.” Every year it brings a tear to my eye to see throngs of people pausing to carry on this tradition at the Derby. It is as if for one brief instant, we’re recalling a collective consciousness and unique identity that all the Saudi Arabian horse traders and slick international gamblers can never take away from us.

“Camptown Races,” “Old Folks at Home,” “Beautiful Dreamer” and “Oh! Susanna” seem as unremarkable to anyone over 40 as an old oaken bucket. Try singing or even mentioning these to anyone under 40; most likely he will look at you like you have two heads.

The songs and stories of America were created for a reason. They taught us about the people who forged a new country in a new land. Dramatic, funny, and sometimes bawdy, each one served its purpose — whether it was teaching about the travails of frontier life or the sweat that laid our railways. They paved the way for a united country as they solidified our common past.

As people throw out their books in lieu of their Kindles, and children learn history from Wikipedia instead of an encyclopedia, one gets the uneasy feeling that everything could be lost with one errant sun-flare. Take comfort in realizing that everything we need to preserve this country isn’t in the Smithsonian or on the internet — it’s in our own minds. Like the wandering book people in Fahrenheit 451, it’s time to preserve that knowledge by repeating it and passing it down. While we can and should build on it, we must never abandon it.

Published in American Thinker:

http://www.americanthinker.com/2013/05/do_you_remember_sweet_betsy_from_pike.html

Photo credit:

Coates, Bob. Photograph of a Conestoga Wagon Parade, Photograph, n.d.; digital images, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Sam Rayburn House Museum, Bonham, Texas.

Authors Picks for Accompanying Music:

ARVE Error: need id and provider

ARVE Error: need id and provider